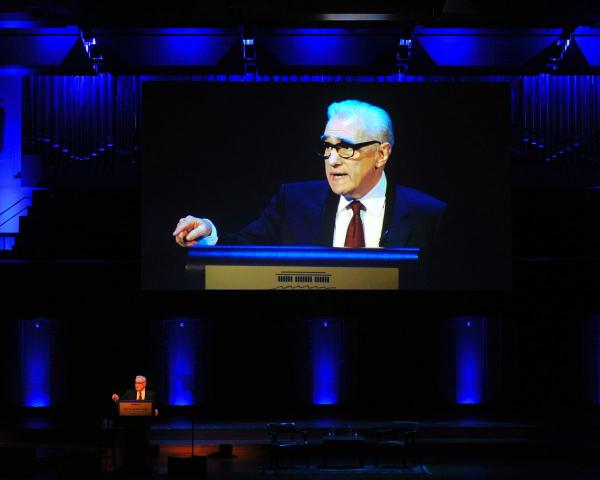

Martin Scorsese

Jefferson Lecture

2013

BY DAVID SKINNER

In a number of interviews, on stage, in print, and on television, Martin Scorsese has already told his life story. The beginning sounds like a script in development, like a Scorsese project that hasn’t yet gone into production.

The family rented a two-story house in Corona, Queens, and lived there happily until Martin’s father, Charles, got into a dispute with the landlord. It involved various people and assorted grievances: brothers and money, and the way certain people act like they’re some kind of big deal. As he told the story to Richard Schickel in Conversations with Scorsese:

The landlord may have felt that my father was involved with underworld figures, which he wasn’t really, but he behaved maybe a little bit like that; my father always liked to dress, you know. And this guy was a man of the earth…. And I think also his wife liked my father. So all this resentment was building up. And then there was a confrontation.

Personal connections had helped the Scorseses move to Queens in the first place, and now they played a part in returning the family to live, as they had once before, with Martin’s grandparents on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. There, in a crowded apartment in the tiny neighborhood of Little Italy, the seven-year-old found himself with less space and less freedom. An asthmatic, he slept in a special tent. On the street he did not fit in. There was, he told Schickel, “an atmosphere of fear.” The local authorities did not wear badges, but they had the power to tell you what to do. And there were rules. The first one was to say nothing.

But it was possible to escape. From a young age, Scorsese was taken to the movies, where he developed a great fondness for studio pictures: westerns, war pics, historical dramas, and some of the greatest movies of the ’40s and ’50s, including Singin’ in the Rain, Sunset Boulevard, Citizen Kane, On the Waterfront, and East of Eden. Just as important was the family television and a program called Million-Dollar Movie, which showed British, French, and Italian films, and replayed them twice a night for a week, enabling the future movie director to watch and rematch great films from abroad.

At New York University—only a few blocks, but a world away from Little Italy—Scorsese began his formal training under Haig Manoogian, to whom he dedicated Raging Bull. There he began I Call First, with future collaborators Harvey Keitel in the lead and Thelma Schoonmaker editing. Finished and reworked after some prodding from Manoogian, it was later renamed Who’s That Knocking at My Door and released as Scorsese’s first feature film. After being rejected by a number of festivals, it was accepted into the Chicago Film Festival and seen by Roger Ebert, who called it “a marvelous evocation of American city life, announcing the arrival of an important new director.”

Ebert has noted that Scorsese received conflicting advice from his mentors. Manoogian told him, “No more films about Italians.” John Cassavetes, whose chatty, improvisational style did much to influence Scorsese’s scripts and production work, told him to “make films about what you know.” Scorsese’s own ambition was to make all kinds of films, like an old-school studio director zipping from one project to the next.

In 1971 Scorsese moved to Hollywood, where he hung out with some of the most promising young directors around: Brian De Palma, Steven Spielberg, and Francis Ford Coppola. He directed Boxcar Bertha, a cut-rate Depression-era film for Roger Corman, the so-called “king of cult film.” Also in Hollywood, Scorsese made Mean Streets, a film about low-level wise guys starring Harvey Keitel and Robert De Niro, whom he had met some years back in New York.

Keitel’s character is guilt-ridden, striving, and in love; De Niro’s Johnny Boy is a violent goofball who seems to have learned how to behave from watching gangster films. One can see here the male camaraderie and tough-guy cross-talk that becomes so important in Scorsese’s later work. In 1976 he made the first of his most enduring films, Taxi Driver, a disturbing character study of Robert De Niro’s antiheroic Travis Bickle, a war veteran and loner whose reaction to the moral malaise of New York City turns increasingly psychotic.

In this period he also directed movies that, despite numerous qualities, seem less like his signature projects, including Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (for which Ellen Burstyn won an Oscar); New York, New York, an expensive homage to old Hollywood that failed commercially and critically; and The Last Waltz, a documentary of the final performance of The Band.

Personal and professional difficulties made this an especially hard period for Scorsese, who was still in his thirties and struggling with his own demons. As things went from bad to worse for the director, Robert De Niro pressed him to make the film that became Scorsese’s masterpiece: Raging Bull, a gorgeous, classic black-and-white film about the savage life and career of boxer Jake LaMotta. It won De Niro an Oscar and confirmed Scorsese’s standing as a great director.

In this hour of triumph, as Raging Bull was showing in film festivals, Scorsese began promoting the cause of film preservation. “Everything we are doing now means nothing!” he said, raising the alarm in one lecture after another, while showing clips to illustrate the damaged quality and fading colors of vintage movie reels.

For a long time the old-fashioned studio director who moved fluidly between genres, like Howard Hawks in the ’40s and ’50s, had been a distant memory. But Scorsese continued to develop a great variety of projects, always as if working out of the mental space of a film buff’s library, but with the conviction of a true artist.

In 1983 he made the artfully dark send-up of celebrity culture, The King of Comedy, in which Robert De Niro and Sandra Bernhard stalk and kidnap a Johnny Carson-type comedian and talk show host played by Jerry Lewis. There was in the next decade a sequel and a remake: The Color of Money boldly followed The Hustler, a beloved classic, 30 years after the original; and with De Niro in 1991, Scorsese remade Cape Fear, the 1962 thriller that had starred Robert Mitchum.

New York City, of course, remained a touchstone. In 1985 Scorsese made the offbeat cult classic After Hours, in which a computer dork played by Griffin Dunne pursues the bohemian Rosanna Arquette and ends up in a series of bizarre misadventures downtown. To the trilogy New York Stories, Scorsese contributed a tart short film starring Nick Nolte as an expressionist painter whose girlfriend realizes that, while serving as his helpmate, she has failed as an artist.

And Scorsese continued exploring new genres, as with The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988, which proved controversial despite the film’s obviously reverent tone. Scorsese was raised Catholic, and in his youth he briefly considered joining a seminary. Father Principe, who had been a mentor to him as a young man, famously said about Taxi Driver, “I’m glad you ended it on Easter Sunday and not on Good Friday.”

In Goodfellas, released in 1990, Scorsese returned to form, creating a gangster movie that is widely regarded as one of the best ever made. Packed with famous lines and scenes, the film is a collection of cinematic jewel pieces stretching over decades of American culture, charting the rise of Henry Hill as a likable street-level operator to his messy decline as a drug dealer and out-of-control addict.

Also in 1990 Scorsese established the Film Foundation, which supports preservation and restoration projects at leading film archives. Several have involved films of personal significance to Scorsese, including The Red Shoes and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, which were directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, and three of John Cassavetes’s films. As always, making his own films did not prevent him from championing the history of the entire medium.

Shame and moral boundaries have always been important in his work—he’s cited James Joyce and Fyodor Dostoyevsky as influences. In 1993 he directed The Age of Innocence, based on Edith Wharton’s scathing novel of manners. Taxi Driver was flecked with ideas from Notes from Underground, and Nicholas Cage in Bringing Out the Dead had enough of a Christ complex to fill out a term paper or two. Fans often remark on Scorsese’s feel for music; there is also a literary flare to his movies. Even Gangs of New York came from a 1920s true crime volume by Herbert Asbury, and The Departed, written by William Monahan, may be one of the most literary of crime films ever. Amid its rueful mix of old loyalties, false identities, fatalism, and betrayal, Frank Costello, played by Jack Nicholson, learns that someone’s mother is not well and unfortunately, “on her way out.”

“We all are,” says Costello, “act accordingly.”

Scorsese’s most recent feature film, Hugo, reminded audiences, however, of his great exuberance for the old Hollywood of high comedy, speeding trains, and achingly sympathetic characters. Shot in 3-D, Hugo was based on Brian Selznick’s illustrated children’s novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret. It tells the story of a young orphan who is reduced to making a life inside the walls of a Paris train station but begins to find his way after discovering a bond with a tinkering toy seller who also happens to be a pioneer of early filmmaking. A movie for children and adults, determined to leave you feeling protective of old movies, Hugo is a love letter to the history of cinema, a history in which Scorsese has for many years now played a leading role.

Click here to read, "With Love and Resolution": An Appreciation.

Like any good film director—or any good artist, really—Martin Scorsese is a magpie. His films are made of bits and pieces picked from everywhere. They are built from personal experience, from observation, from the books he’s read and the rock ’n’ roll he loves and, of course, from the life he’s lived in the dark, watching other people’s films.

This intertextual referentiality is in itself nothing unique, certainly not in the filmmaking of the “movie brat” directors of Scorsese’s generation, whose ranks include Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma and Peter Bogdanovich and Scorsese’s own collaborator, Paul Schrader. What is unusual is the degree to which Scorsese, rather than covering his tracks and effacing his influences to draw greater glory upon his wholly original genius, has made those influences a matter of public record. “I saw these movies,” Scorsese says, straightforwardly as ever, in his 1999 My Voyage to Italy. “They had a powerful effect on me. You should see them.”

Scorsese is, by almost universal consensus, one of our best directors, consistently posing fresh challenges to himself and his audience. But as he has become, more and more, an American institution, Scorsese has traded in on his fame for a second job, fashioning himself as something like the official spokesman for movie love. In locating his own films in relation to those of his forebears, in framing his extraordinary career as another chapter in a grand tradition, Scorsese has used his prominence to encourage his audience to look back at what has come before, to see the whole tapestry of film history. Scorsese has pointed out that Raging Bull comes out of On the Waterfront and Abraham Polonsky’s Body and Soul; that the way the soundtrack works in Goodfellas was inspired by the synthesis of music and image in Michael Powell’s Tales of Hoffman; that Taxi Driver contains telltale traces of Michelangelo Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her, and, ever the cultural democrat, a 1949 John Payne western called El Paso.

Scorsese’s impulse to return to and repurpose the images that had left a mark on him was evident from the get-go: In his 1973 Mean Streets, small-time gangsters escape Little Italy for Monument Valley at a showing of John Ford’s The Searchers. Scorsese doesn’t only pay homage, but shows how movies and other pop influences operate within his characters’ lives, illustrating the dialog between a society and the pop it produces.

Every film lover has a moment when they begin a dialog of their own, engaging with the medium not just in its present tense, but as part of an ongoing story, a story that has now been in the telling for almost one hundred twenty years. For Scorsese, the key to this transition from moviegoer to budding movie scholar was the extensively illustrated 1949 edition of A Pictorial History of the Movies by Deems Taylor, which Scorsese compulsively checked out from the Tompkins Square Library as a young man, finally returning it with a few stills suspiciously snipped out. The director confesses to his sin in A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies, a three-part 1995 documentary produced by the British Film Institute, which has Scorsese breathlessly narrating the story of our national film history. The effectiveness of this project owes much to Scorsese’s selection of clips, showcasing the “strong, bold” and “overwhelming” images that he favors, but also to his powers as a raconteur: His infectious enthusiasm and the emotion of his rapid-fire direct address make this exhortation on behalf of the works that he loves intense, impassioned, and urgent.

If it gets you at the right time, A Personal Journey is one-stop shopping for the novice cinema aesthete, a checklist to work your way through: Allan Dwan and Delmer Daves and Scarlet Street and too many other subjects-for-further-research to name. If you were from a previous generation, you might have, in the same way, referred to Scorsese’s answers in the now-defunct “Guilty Pleasures” feature from a 1978 Film Comment, in which he told of his passion for Howard Hawks’s little-loved Land of the Pharaohs. (One of the most endearing things about Scorsese is the extreme catholicity of his taste—when auditioning for Scorsese’s Casino, drive-in expert Joe Bob Briggs remembers the director quizzing him on “women-in-prison” films.)

A Personal Journey was followed by My Voyage to Italy, in which Scorsese recalled his introduction to the cinema of his ancestral country: As a child in New York City, he spent evenings with his extended family around the 16" black-and-white RCA Victor television set, watching Friday-night broadcasts of Italian-language films. More recently, Scorsese has collaborated with the critic Kent Jones on documentaries about great filmmakers, narrating 2007’s Jones-directed Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows and codirecting 2010’s A Letter to Elia, addressed to “Gadge” Kazan, whose On the Waterfront and its street-corner patois left an indelible impression on Scorsese. And while those works address a fairly self-selecting audience of cinephiles, it should be noted that Scorsese’s most recent movie, Hugo, was a tribute to the art of Georges Méliès, a French filmmaker of the early silent period—and it did almost $200 million of business in multiplexes and malls.

While proselytizing for film history, Scorsese has simultaneously been a crucial figure in assuring that the physical elements of that history will be around for future generations to rediscover. Fading in color film stock was once a concern limited to the world of archivists, but Scorsese brought it to public attention throughout the 1980s, petitioning Eastman Kodak and agitating in the industry. This move into public advocacy led to Scorsese’s crucial role in the 1990 creation of the Film Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to funding preservation projects, directly responsible for restoring more than five hundred titles to date. While the Film Foundation has principally focused on American film, Scorsese’s chairmanship of the newly created World Cinema Foundation in 2007 widened his purview to preservation in developing countries. Recognizing that any movement benefits from having an official face, preferably a famous one, Scorsese lent his to the cause of film preservation, and he has never backed away from his commitment.

Scorsese’s work to reveal the inextricable ties between film present and film past doesn’t mean that his relationship with cinema is strictly backward-looking, for he has been a friend to many contemporary filmmakers. He has underwritten careers, including that of Kenneth Lonergan. In a 2000 Esquire piece asking critics to name “the next Scorsese,” Scorsese himself prophetically voted for Wes Anderson. (This was before The Royal Tenenbaums.) Scorsese portrayed Van Gogh for Kurosawa and “presented” both Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah and the Swedish crime film Easy Money. Now undeniably a global figure, he will place his executive producer imprimatur on Luc Besson’s latest and on a new film from Hong Kong’s Andrew Lau, whose Infernal Affairs Scorsese remade as The Departed.

Money talks, but selfless curiosity is, finally, what drives the conversation and the culture. Certainly Scorsese has never forgotten his debt to his own teachers—the Million-Dollar Movie on New York’s Channel 9; his mentor at NYU and the author of The Film-Maker’s Art, Haig P. Manoogian; maverick filmmaker John Cassavetes. We have, so many of us, learned and benefited from Scorsese’s selfless curiosity and inexhaustible appetite for celluloid, in ways that we may not even recognize. And we are still learning.

[film clip: The Magic Box, by John Boulting]

That scene was from a picture called The Magic Box, which was made in England in 1950. The great English actor Robert Donat plays the inventor William Friese-Greene – he was one of the people who invented movies. The Magic Box was packed with guest stars. It was made for an event called the Festival of Britain. You had about 50 or 60 of the biggest actors in England at the time, all doing for the most part little cameos, including the man who played the policeman – that was Sir Laurence Olivier.

I saw this picture for the first time with my father. I was 8 years old. I’ve never really gotten over the impact that it had. I believe this is what ignited in me the wonder of cinema, and the obsession – of watching movies, making them, inventing them.

Friese-Greene gives everything of himself to the movies, and he dies poor. He dies a pauper. That line – “You must be a very happy man, Mr. Friese-Greene” –of course is ironic, knowing the full story of his life, but in some ways it’s also true because he’s followed his obsession all the way. So it’s both disturbing and inspiring. I was very young. I couldn’t put this into words when I saw this, but I sensed them. I sensed these ideas and these things and saw them up there on the screen.

My parents had a good reason for taking me to the movies all the time, because I was always sick with asthma since I was three years old and I apparently couldn’t do any sports, or that’s what they told me. But really, my mother and father did love the movies. They weren’t in the habit of reading, that didn’t really exist where I came from, and so we connected through the movies.

And over the years I know now that the warmth of that connection with my family and with the images up on the screen gave me something very precious. We were experiencing something fundamental together. We were living through the emotional truths on the screen together, often in coded form, these films from the 40s and 50s sometimes expressed in small things, gestures, glances, reactions between the characters, light, shadow. We experienced these things that we normally couldn’t discuss or wouldn’t discuss or even acknowledge in our lives.

And that’s actually part of the wonder. Whenever I hear people dismiss movies as “fantasy” and make a hard distinction between film and life, I think to myself that it’s just a way of avoiding the power of cinema. Of course it’s not life – it’s the invocation of life, it’s in an ongoing dialogue with life.

Frank Capra said, “Film is a disease.” He went on, but that’s enough for now. I caught the disease early on. I used to feel it. They used to take me to the movies all the time. I used to feel it whenever we walked up to the ticket booth with my mother or my father or my brother. You’d go through the doors, up the thick carpet, past the popcorn stand that had that wonderful smell - then to the ticket taker, and then sometimes these doors would open in the back and there’d be little windows in it in some of the old theaters and I could see something magical happening up there on the screen, something special. And as we entered, for me it was like entering a sacred space, a kind of a sanctuary where the living world around me seemed to be recreated and played out.

What was it about cinema? What was so special about it? I think I’ve discovered some of my own answers to that question a little bit at a time over the years.

First of all, there’s light.

Light is at the beginning of cinema, of course. It’s fundamental - because it’s created with light, and it’s still best seen projected in dark rooms, where it’s the only source of light. But light is also at the beginning of everything. Most creation myths start with darkness, and then the real beginning comes with light – which means the creation of forms. Which leads to distinguishing one thing from another, and ourselves from the rest of the world. Recognizing patterns, similarities, differences, naming things - interpreting the world. Metaphors – seeing one thing “in light of” something else. Becoming “enlightened.” Light is at the core of who we are and how we understand ourselves.

And then, there’s movement…

I remember when I was about five or six, somehow I was able to see someone project a 16mm cartoon on a small projector, and I was allowed to look inside the projector. I saw these little still images passing mechanically through the gate at a very steady rate of speed. In the gate they were upside down, but they were moving, and on the screen they came out right side up, moving. At least it was there was the sensation of movement. But it was more than that. Something clicked, right then and there. “Pieces of time” – that’s how James Stewart defined movies in a conversation with Peter Bogdanovich. That wonder I felt when I saw these little figures move – that’s what Laurence Olivier feels when he watches those first moving images in that scene from The Magic Box.

[slide: bison, cave paintings of Chauvet] The desire to make images move, the need to capture movement, seems to be with us 30,000 years ago in the cave paintings at Chauvet – as you can see it here, in this image the bison appears to have multiple sets of legs. Maybe that was the artist’s way of creating the impression of movement. I think this need to recreate movement is a mystical urge. It’s an attempt to capture the mystery of who and what we are, and then to contemplate that mystery.

Which brings us to the boxing cats. [film clip: cats boxing, filmed by T. Edison in 1894] This appears to be two cats boxing. It was shot in 1894, in Thomas Edison’s Black Maria studio that he had in New Jersey – it was actually it was just a little shack. This is one among hundreds of little scenes that he and his team recorded in the studio with his Kinetograph.

It’s probably one of the lesser known scenes – there are better-known ones of a blacksmith, the heavyweight champion Jim Corbett boxing, Annie Oakley, the great sharpshooter from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. At some point, somebody had the idea to do two cats boxing – apparently this was what went on in New Jersey at the time.

Edison, of course, was one of the people who invented film. There’s been a lot of debate about who really invented film – there was Edison, the Lumière Brothers in France, Friese-Greene and R.W. Paul in England. And actually you can go back to a man named Louis Le Prince who shot a little home movie in 1888.

And then you could go back even further to the motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge, [slide: E. Muybridge’s photos of horses running] which were made in the 1870s, 1880s – he would set a number of still cameras side by side and then he’d trigger them to take photos in succession, of people and animals in movement. His employer Leland Stanford bet him that all four of a horse’s hooves do not leave the ground when the horse is running.

As you can see, Muybridge won the bet. All four hooves do leave the ground at the same time while the horse is galloping.

Does cinema really begin with Muybridge? Or should we go all the way back to the cave paintings? In his novel Joseph and his Brothers, Thomas Mann writes, “The deeper we sound, the further down into the lower world of the past we probe and press, the more do we find that the earliest foundations of humanity, its history and culture, reveal themselves unfathomable.” All beginnings are unfathomable – the beginning of human history, the beginning of cinema.

[film clip: 1895 film of train arriving in station by Lumière Brothers] This film, by the Lumière Brothers in France, is commonly recognized as the first publicly projected film. It was shot in 1895. When you watch it, it really is 1895. The way they dress and the way they move. It’s now and it’s then, at the same time. And that’s the third aspect of cinema that makes it so uniquely powerful – it’s the element of time. Again, pieces of time.

[film clip: from Hugo, by M. Scorsese] When we made the movie Hugo, we went back and tried to recreate that first screening, when people were so startled to see this image that they jumped back. The thought the train was going to hit them.

When we studied the Lumière film, we could see right away that it was very different from the Edison films. They weren’t just setting up the camera to record events or scenes. This film is composed. When you study it, you can see how carefully they placed the camera, the thought that went into what was in the frame and what was left out of the frame, the distance between the camera and the train, the height of the camera, the angle of the camera – what’s interesting is that if the camera had been placed even a little bit differently, the audience probably wouldn’t have reacted the way they did. In Hugo, we converted the Lumière film to 3-D, and we combined it with our 3-D image, but it didn’t have the same effect. We discovered we had to do it in two dimensions within a 3-D image, because the composition by the Lumière Brothers was designed to create the illusion of depth within a flat surface.

So in essence, the Lumières weren’t just recording events the way they did in Edison’s studio, they were really interpreting reality and telling a story with just one angle.

And of course so was Georges Méliès. [film clip: G. Méliès’ Impossible Voyage]

Méliès began as a magician and his pictures were made to be a part of his live magic act. He created trick photography and incredible handmade special effects, and in so doing he sort of remade reality – the screen in his pictures is like opening a magic cabinet of curiosities and wonders.

Now, over the years, the Lumières and Méliès have been consistently portrayed as opposites – one filmed reality, the other created special effects. Of course this happens all the time – it’s a way of simplifying history. But in essence, they were both heading in the same direction, just taking different roads – they were taking reality and interpreting it, re-shaping it, and trying to find meaning in it.

And then, everything was taken further with the cut. [film clip: Great Train Robbery] Who made the first cut from one image to another – meaning, a shift from one vantage point to another with the viewer understanding that we’re still within one continuous action?

Again, to quote Thomas Mann – “unfathomable.” But as far as we know, this is one of the earliest and most famous examples of a cut, from Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 milestone film The Great Train Robbery. Even though we cut from the interior of the car to the exterior, we know we’re in one unbroken action.

And this film [film clip: The Musketeers of Pig Alley by D. W. Griffith] is one of the dozens of one-reel films that D.W. Griffith made in 1912 – it’s a remarkable film called The Musketeers of Pig Alley. It’s commonly referred to as the first gangster film, and actually it’s a great Lower East Side New York street film. Now if you watch, the gangsters are crossing quite a bit of space before they get to Pig Alley, which is actually a recreation of a famous Jacob Riis photo of Bandit’s Roost from Five Points, but you’re not seeing them cross that space on the screen.

Yet, you are seeing it. You’re seeing it all in your mind’s eye, you’re inferring it. And this is the 4th aspect of cinema that’s so special. That inference. The image in the mind’s eye.

For me it’s where the obsession began. It’s what keeps me going, it never fails to excite me. Because you take one shot, you put it together with another shot, and you experience a third image in your mind’s eye that doesn’t really exist in those two other images – the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein wrote about this, and it was at the heart of all the films he did. This is what fascinates me – it’s frustrating sometimes, it’s always exciting - if you change the timing of the cut even slightly, by just a few frames, or even one frame, then that third image in your mind’s eye changes too. And that has been called, appropriately, I believe, film language.

[film clip: Intolerance, by D. W. Griffith] In 1916, D. W. Griffith made a picture – an epic – called Intolerance, in part as an act of atonement for the racism in The Birth of a Nation. Intolerance ran about three hours. But he goes further with the idea of the cut, he shifts between four different stories – the first story is the massacre of the Hugenots, the second story is the passion of Christ, the third is a spectacle really, the fall of Babylon, and a fourth story which was a modern American story set in 1916. Now at the end of the picture, what Griffith did is that he cut between the different climaxes of these different stories – he cross-cut through time, something that had never been done before. He tied together images not for story or narrative purposes but to illustrate a thesis: in this case, the thesis was that intolerance has existed throughout the ages and that it is always destructive. Eisenstein later wrote about this kind of editing and gave it a name – he called it “intellectual montage.”

For the writers and commentators who were very suspicious of movies – because after all it did start as a Nickelodeon storefront attraction - this was the element that signified film as an art form. But of course, it already was an art form – that started with the Lumières and Méliès and Porter. This was just another, logical step in the development of the language of cinema.

That language has taken us in many directions.

For instance, here, [film clip: Love Song, by Stan Brakhage] into the pure abstraction of the extraordinary avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage. Or here –[film clip: Cisco commercial] This is a commercial, very well done by the visual artist and filmmaker Mike Mills, made for an audience that’s seen thousands of commercials – the images come at you so fast that you have to make the connections after the fact.

Film language has also taken us here [film clip: 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Stanley Kubrick]

This is the Stargate sequence from Stanley Kubrick’s monumental 2001: A Space Odyssey. Narrative, abstraction, speed, movement, stillness, life, death - they’re all up there. Again, we find ourselves back at that mystical urge – to explore, to create movement, to go faster and faster, and maybe find some kind of peace at the heart of it, a state of pure being.

But the cinema we’re talking about here – Edison, the Lumière Brothers, Méliès, Porter all the way through Griffith, and on through Kubrick – that’s really almost gone. It’s been overwhelmed by moving images coming at us all the time and absolutely everywhere, even faster than the visions coming at the astronaut in the Kubrick picture.

Classical cinema, as it’s come to be called, now feels like the grand opera of Verdi or Puccini. And we’re no longer talking about celluloid – that really is a thing of the past. For many film lovers, this is a great sadness and a sense of loss. I certainly feel it myself – I grew up with celluloid and its particular beauty, and its idiosyncrasies.

But cinema has always been tied to technological development, and if we spend too much time lamenting what’s gone, then we’re going to miss the excitement of what’s happening now. Everything is wide open. To some, this is cause for concern. But I think it’s an exciting time precisely because we don’t know what tomorrow will bring, let alone next week.

And we have no choice but to treat all these moving images coming at us as a language. We need to be able to understand what we’re seeing, and find the tools to sort it all out.

We certainly agree now that verbal literacy is necessary. But a couple of thousand years ago, Socrates actually disagreed – his argument was almost identical to the arguments of people today who object to the internet, who think that it’s a sorry replacement for real research in a library. In the dialogue with Phaedrus, written by Plato, Socrates worries that writing and reading will actually lead to the student not truly knowing it –that once people stop memorizing and start writing and reading, they’re in danger of cultivating the mere appearance of wisdom rather than the real thing.

Now we take it for granted – reading and writing are taught in schools - but the same kinds of questions are coming up around moving images: Are they harming us? Are they causing us to abandon written language?

We’re face to face with images all the time in a way that we never have been before. And that’s why I believe we need to stress visual literacy in our schools. Young people need to understand that not all images are there to be consumed like fast food and then forgotten – we need to educate them to understand the difference between moving images that engage their humanity and their intelligence, and moving images that are just selling them something. In fact, as Steve Apkon, the film producer and founder of The Jacob Burns Film Center in Pleasantville, NY, points out in his new book The Age of the Image, the distinction between verbal and visual literacy needs to be done away with, along with the tired old arguments about the word and the image and which is more important. They’re both important. They’re both fundamental. Both take us back to the core of who we are.

[slide: image of Sumerian tablet] When you look at ancient writing, words and images are almost indistinguishable. In fact, words are images, they’re symbols. Written Chinese and Japanese still seem like pictographic languages.

And at a certain point – exactly when is… “unfathomable” – words and images diverged, like two rivers, or two different paths to understanding.

But in the end, there really is only literacy.

At The Film Foundation, which I founded in 1990, we developed a curriculum called “The Story of Movies,” which we make available for free to any teacher who wants it. So far, 100,000 educators have used it in their classrooms.

[film clip: The Day the Earth Stood Still, by Robert Wise] We’ve created three study units around certain titles, one of which is a 1951 film called The Day the Earth Stood Still. Which, as you can see, was shot not too far from here. Why this picture? Because it’s beautifully made in black and white. Because it’s Hollywood at its best during the era that, I think, really deserves the name Golden Age. Because it’s one of the really great science fiction pictures of the 50s. And there’s another reason.

The American film critic Manny Farber said that every movie transmits the DNA of its time. The Day the Earth Stood Still was made right in the middle of the Cold War, and it has the tension, the paranoia, the fear of nuclear disaster and the fear of the end of life on planet earth, and a million other elements, more difficult to put into words. These elements have to do with the play of light and shadow, the emotional and psychological interplay between the characters, the atmosphere of the time woven into the action, the choices that were made behind the camera and that resulted in the immediate film experience for viewers like myself and my parents. These are the aspects of a film that reveal themselves in passing, the things that bring the movie to life for the viewer. And the experience becomes even richer when you explore these elements much more closely.

But what happens when a movie is seen out of its time? For me, 1951 was my present when I saw it. I was nine. For someone born 20 years later, it’s a different story.

For someone born today, they’ll see it with completely different eyes and a whole other frame of reference, different values, uninhibited by the biases of the time when the picture was made. You can only see the world through your own time – which means that some values disappear, and some values come into closer focus. Same film, same images, but in the case of a great film the power – a timeless power that really can’t be articulated – that power is there even when the context has completely changed.

[slide: image of Sumerian tablet] But, in order to experience something and find new values in it, it has to be there in the first place - you have to preserve it. All of it. Archeologists have made many discoveries by studying what we throw away, the refuse of earlier civilizations, the things that we consider expendable.

For example, this Sumerian tablet. It’s not a poem, it’s not a legend. It’s actually a record of livestock – a balance sheet of business transactions. Miraculously, it’s been preserved, for centuries, first under layers of earth and now in a climate-controlled environment. When we still find objects like this, we immediately take great care with them.

We have to do the same thing with film. [slides: series of images of decayed film]

But film isn’t made of stone. Until recently, it was all made of celluloid, as I said before – thin strips of nitrocellulose, the first plastic compound. Through the late 1940s, before nitrate film was replaced by safety film, nitrate film caught fire, it blew up - it could turn to powder and explode. In 1950 it was replaced with safety stock.

And with a few exceptions, preservation wasn’t even discussed at that time– it was something that happened by accident. Some of the most celebrated movies were the victims of their own popularity. Every time they were re-released, they were often printed from the original negatives, and in the process they were run into the ground. Film is so fragile – that didn’t really sink in at the time.

It wasn’t so long ago that nitrate films were melted down just to get the silver content back. Prints of films made in the 70s and 80s were recycled to make guitar picks and plastic heels for shoes.

That’s a disturbing thought – just as disturbing [slide: photo by Mathew Brady from Civil War battlefield] as knowing that those extraordinary glass photographic plates taken of the Civil War not long after the birth of photography were later sold to gardeners for building greenhouses. Whatever plates survived are here in the Library of Congress.

So when I hear the question – and interestingly enough some people are still asking it – “why preserve anything?” – I just think of those stories. All that silent film, all those images of the Civil War, and there was no consciousness of their lasting value. That only came later. Why preserve? Because we can’t know where we’re going unless we know where we’ve been – we can’t understand the future or the present until we have some sort of grappling with the past.

I became involved with the cause of preservation in the early 1980s, when I really understood just how fragile film was. Since the early 90s, around the time we formed The Film Foundation, which was an idea by Bob Rosen to put all of us together, myself and a number of other directors, Spielberg, and Lucas and Coppola and Robert Redford, Sydney Pollack… The Film Foundation was formed to bring the studios together with the archives.

Since that time I think there actually has been a shift in consciousness and much more awareness of the need for preservation, which is ongoing – because it isn’t something that’s done once. You have to keep going back, constantly, moving the films from one format to another, to make sure they survive, because it’s an endless process. Today, we have some really wonderful tools. When the time came to restore Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, [film clip: The Red Shoes, by Powell & Pressburger] one of my very, very favorite films and one of the best films ever made, we were fortunate enough to have these tools at our disposal.

I thought I would just show you a little bit of the restoration demonstration Thelma Schoonmaker put together for the Blu- Ray of that film, to give you an idea of the work involved. It took years to get this going and was quite expensive. You must bear in mind that The Red Shoes was shot in the old three-strip Technicolor technology with very heavy cameras that had not one but three rolls of film going through them at the same time.

[film clip: on the restoration of The Red Shoes] None of this would have been possible before digital technology. But I have to say that we are too late. Over 90% of all silent cinema is gone. Lost forever. Every time a silent picture by some miracle turns up like John Ford’s film he made in 1927 called Upstream, which was recently discovered by the National Film Preservation Foundation in an archive in New Zealand – every time one of those shows up we have to remind ourselves that there are hundreds, maybe thousands more that are gone forever. So we have to take really good care of what’s left. Everything, from the acknowledged masterworks of cinema to industrial films and home movies, anthropological films. Anything that could tell us who we are.

And here’s one example of why we have to look beyond the officially honored, recognized, and enshrined - why we have to preserve everything systematically

[film clip: Vertigo, by Alfred Hitchcock] This is a 1958 picture directed by Alfred Hitchcock that I’m sure many of you have seen, called Vertigo. When this film came out, some people liked it, some didn’t, and then it just went away. Even before it came out, it was classified as another picture from the Master of Suspense and that was it, end of story. Almost every year at that time, there was a new Hitchcock picture – it was almost like a franchise.

At a certain point, there was a reevaluation of Hitchcock, thanks to the critics in France who later became the directors of the French New Wave, and to the American critic Andrew Sarris. They all enhanced our vision of cinema and helped us to understand the idea of authorship behind the camera.

When the idea of film language started to be taken seriously, so did Hitchcock. Because his films seemed to have an innate sense of visual storytelling. And the more closely you looked at his pictures, the richer and more emotionally complex they became.

Ironically, as people were starting to recognize Hitchcock’s genius, several of his most important pictures were suddenly unavailable. This was in 1973. Vertigo was one of them. There were a number of films: Rear Window, Rope…

At the time, no one understood what had happened, we couldn’t see these films anymore, not even on television. In fact, Hitchcock himself pulled the films from distribution so that he could get his estate in order. There were secret screenings, some people had private prints here and there in New York and L.A. In the case of Vertigo that only added to the mystique of the picture.

When it came back into circulation, in 1984, along with the other films that had been held back, it needed work but the new prints weren’t made from the original negative and the color was completely wrong. The color scheme of Vertigo is extremely unusual, and this was a major disappointment. In the meantime, the elements – the original negatives - needed serious attention.

Ten years later, Bob Harris and Jim Katz did a full-scale restoration for Universal. It was very expensive. The picture was originally shot in the Vista-Vision process, and so they had to do their restoration in 70mm, which was as close as you could get to VistaVision – because that format is gone now. At that point, they had to work from extremely damaged sound and picture elements. But at least, a major restoration had been done.

As the years went by, more and more people saw Vertigo and came to appreciate its hypnotic beauty and very strange, obsessive focus. Obsessive… focus…

[film clip: Vertigo, by Hitchcock] A man is hired to follow a woman. The woman appears to be haunted by the legend of her great-grandmother and that woman’s tragic life. She goes into trances, absences that put her in danger. She sees a vision of her own death in an old mission in northern California that has a bell tower. He brings her there to cure her. She climbs the tower, he tries to go after her but he can’t because he suffers from vertigo, and he just watches, helplessly, as she jumps to her death.

That’s just the first half of the film. And that’s only the plot. As in the case of many great films, maybe all of them, we don’t keep going back for the plot. Vertigo is a matter of mood as much as it’s a matter of storytelling – the special mood of San Francisco where the past is eerily alive and around you at all times, the mist in the air from the Pacific that refracts the light, the unease of the hero played by James Stewart in the lead, Bernard Herrmann’s haunting score. And, as the film critic B. Kite wrote, you haven’t really seen Vertigo until you’ve seen it again – so for those of you who haven’t seen it even once, when you do, you’ll know what I mean.

In 1952, the British film magazine Sight and Sound started conducting a poll. They do it every ten years now. They asked film people from around the world – directors, writers, producers, critics – to list what they thought were the ten greatest films of all time, and then they tallied the results and published them. In 1952, number one was Vittorio de Sica’s great Italian Neorealist picture Bicycle Thieves. Ten years later, in 1962, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane was at the top of the list. It stayed there for the next forty years. Citizen Kane is a masterpiece, of course. It was released in 1941 with a lot of fanfare, and while it wasn’t a great financial success, it was generally regarded as a milestone in the art of cinema, re-discovered in the 50s by my generation, on television actually, and considered one of the greatest films ever made. It still is. It was also regarded as an essentially American picture about drive, ambition, failure, and, again, like Vertigo, time.

As I said, Citizen Kane was number one for forty years. Until last year, 2012, when it was displaced by a movie that came and went in 1958, and that came very, very close to being lost to us forever –and that’s Vertigo. And by the way, so did Citizen Kane – because the original negative was burned in a fire in the mid-70s in LA.

So, my point is not only do we have to preserve everything, but most importantly, we can’t afford to let ourselves be guided by cultural standards – particularly now. There was a time when the average person wasn’t even aware of box office grosses. But since the 1980s, it’s become a kind of sport – and really, a form of judgment. It culturally trivializes film.

And for young people today, that’s what they know. Who made the most money? Who was the most popular? Who is the most popular now, as opposed to last year, or last month, or last week? Now, the cycles of popularity are down to a matter of hours, minutes, seconds, and the work that’s been created out of seriousness and real passion is lumped together with the work that really hasn’t.

And then, amidst all this chaos, we have to remember: we may think we know what’s going to last and what isn’t. We may feel absolutely sure of ourselves, but we really don’t know, we can’t know. We have to remember Vertigo, and the Civil War plates, and that Sumerian tablet.

And also remember that Moby-Dick sold very few copies when it was printed in 1849, that many of the copies that weren’t sold were destroyed in a warehouse fire, that it was dismissed by many, and that Herman Melville’s greatest novel, one of the greatest works in literature, was only reclaimed in the 1920s.

We also have to think about where we are now.

We need to remember that there are other values beyond the financial, and that our American artistic heritage has to be preserved and shared by all of us.

Just as we’ve learned to take pride in our poets and writers, in jazz and the blues, we need to take pride in our cinema, our great American art form.

Granted, we weren’t the only ones who invented the movies. We certainly weren’t the only ones who made great films in the 20th century, but to a large extent the art of cinema and its development has been linked to us, to our country. That’s a big responsibility. And we need to say to ourselves that the moment has come when we have to treat every last moving image as reverently and respectfully as the oldest book in the Library of Congress.

Thank you.

The National Endowment for the Humanities would like to thank the following donors for their sponsorship of the 2013 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities: